During a recent lecture held at the West Malling campus, Rev Dr Lesley Hardy took guests on an incredible journey through time to explore the life – and surprisingly recent legacy – of Folkestone’s patron saint, St Eanswythe.

In this piece, we reflect on the illusive subject of Dr Hardy’s lecture – including how she and her fellow archaeologists got up close and personal with the real Eanswythe.

When Dr Hardy first stepped up to lead the Finding Eanswythe project, she and her team expected to discover only the historical aspects of St Eanswythe’s life.

However, the project took a surprising turn, leading to a discovery of St Eanswythe’s 600+ year old relics.

Why is St Eanswythe so important to the people of Folkestone?

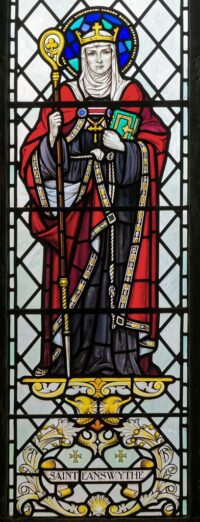

Stained glass in the Eanswythe Chapel at St Mary and St Eanswythe Church, by C E Kempe.

The project, which became known as Finding Eanswythe, came to be after another archaeological project, excavating a Roman villa, came to an end.

Dr Hardy and her team found themselves sitting in the British Lion; a pub in the historic town centre of Folkestone, asking themselves the question, “What next?”. One big unanswered question was the town’s patron saint – Eanswythe. She was an enduring symbol, but no one knew much about her.

The archaeological team began the process of trying to understand her, her history, and her life. They wanted to understand how St Eanswythe was remembered and how she was forgotten.

At the start of the project, it was almost impossible to find anything related directly to the saint, as she was “lost in mists of time”. Little did they realise they would end up coming in direct contact with the saint’s mortal remains.

The life of St Eanswythe, Anglo-Saxon princess

Eanswythe was the daughter of Queen Emma and King Eadbald and granddaughter of Ethelbert; the Anglo-Saxon king who first welcomed St Augustine upon his arrival in 597.

Eanswythe grew up around the birth of English Christianity. She came from the Kentish Royal Dynasty, which was pagan until the arrival of Pope Gregory the Great. Eanswythe’s father, Eabald, renounced Christianity in around 616; although he reversed his decision a few years later.

Kentish Royal Legend – a record about Kentish royal saints – credits St Eanswythe with establishing a monastery or minster on the Vale, in Folkestone. The monastery is considered to have been a “mixed house”, with both religious women and male lay people being part of the community.

Eanswythe is believed to have been one of the first women to have established such a monastery in England; a significant feat considering she is thought to have died between the ages of 17 and 22.

The St Eanswythe monastery and the patron saint’s relics

Window of St Eanswythe in St Mary and St Eanswythes Church, by G.E.R Smith

After her death between 650 and 660, Eathwythe was venerated by the local people as a saint.

She was one of the local saints, or “patron saints”, as people called them; someone who was significant to your community, who could advocate for you in Heaven.

As part of this tradition, some of Eanswythe’s physical remains were retained at the minster she founded and held within a relic. In the case of Eanswythe, the relic was a head reliquary; a vessel made of precious metal, studded with jewels, in the shape of Eanswythe’s head.

The original minster was built on the headland, overlooking the sea. The reason for its destruction is unclear – it may have fallen into the sea or been sacked by Vikings – but it was later relocated further inland.

The new church was christened the Church of St Mary and St Eanswythe, and became the new home of Eanswythe’s relics.

How the memory of Eanswythe was saved

During the Reformation, the veneration of saints became illegal and shrines and altars were destroyed, along with relics. As Dr Hardy related during the talk, unfortunately, the relic of Eanswythe was thought to be no exception.

Despite this, the memory of Eanswythe lived on. It was even rumoured that her body was buried somewhere in Folkestone and in 1660, a stone coffin was found in the floor of the church with an unidentified woman’s body inside. Believing it to be the lost tomb of St Eanswythe, people cut locks of her hair as sacred keepsakes.

Over 200 years later in 1885, another discovery was made. During cosmetic work being carried out in the church, workmen found a secret compartment in a wall. Inside was a reliquary of Eanswythe – an ancient leaden box containing the saint’s remains.

It’s believed that during the reformation, someone put Eanswythe’s remains in an old Roman casket and hid it in the wall, in an effort to save the relic from destruction by Cromwell’s men.

Carbon dating mysterious remains found in the Church of St Eanswythe

Dr Hardy’s project Finding Eanswythe were able to trace much of Eanswythe’s life – and eventful afterlife! – but as she explained, she and her team were able to solve more of the puzzle.

The team wanted to know if the remains found in 1885 were really of St Eanswythe. People frequently venerated relics that turned out to be from a different person or even an animal.

In 2020, the Finding Eanswythe team performed a series of tests on the bones, including DNA tests, isotopic analysis and carbon dating. These tests confirmed that the remains found within the walls of the church were indeed Eanswythe’s.

The team talk about their experiences of the investigation and what their coming in contact with the relics meant for them in the YouTube video, Three days in January. You can watch the video via the YouTube player below.

Where memory, theology and history meet

This project combined archaeology and theology, uncovering both the history of St Eanswythe and the town of Folkestone.

As Dr Hardy emphasised in her closing remarks, all churches have stories and memories. Churches are memory places for many communities, where memories are retained and venerated.

As such, people training to be priests become custodians of those memories. Dr Hardy encouraged attendees to approach this duty with respect, care, and an open-mind, historically speaking.

Even if people don’t consciously understand what the church means, they will on some level. As Dr Rev Lesley Hardy emphasised, churches are communal place that preserves history and memory; which is why history, archaeology and heritage is so integral to the training received by ordinands.

St Augustine’s College of Theology wishes to extend our warmest thanks to Dr Rev Lesley Hardy for time and for sharing the story of St Eanswythe with us.

While you may not have been able to attend Finding Eanswythe: the Life and Afterlife of an Anglo-Saxon Saint, you can explore our range of upcoming events today.